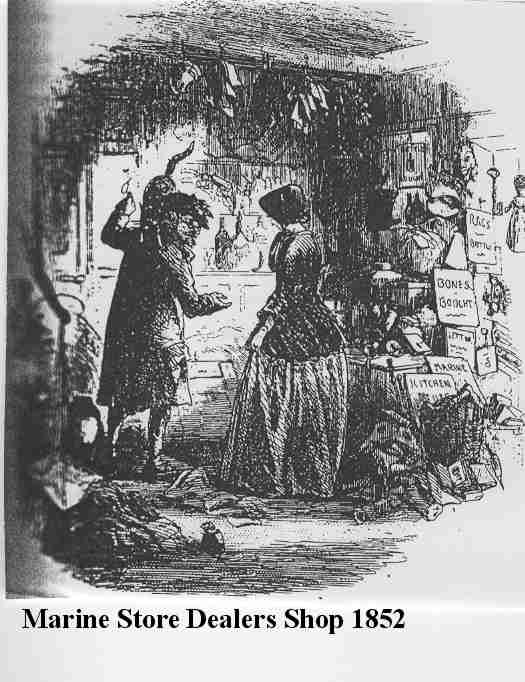

But before very long he appears in Trade Directories as a "Marine Store Dealer"-(a misleading and grandiloquent term for a grubby, if useful, business). The change occurs in the 1860s, though occasionally in other places he still refers to himself as a tailor. It isn't too difficult to see how this might come about, given all the circumstances.

The original Marine Store Dealers, as the name suggests, were traders in all manner of ships' and mariners' supplies, not only for fitting out voyages, but also selling off the surplus and second-hand goods to the general public --anything from the proverbial 'old rope', to old anchor chains, pork barrels and sailors' canvas trousers. Also, it was usual for unmarried seamen to pawn all their on-shore possessions before a lengthy voyage, and the dealers would sell off the unredeemed items. It is largely from this side of the trade that the later 'Marine Store Dealers' evolved. By the end of the eighteenth-century, and all through the nineteenth,

'Marine Store Dealer' had

become a generic term for any kind of miscellaneous second-hand merchant supplying the

'lower orders'. It would be misleading to think of this as a peripheral trade, like junk

shops of the next century --which in some respects they resembled --because the majority

of poorer people were almost entirely reliant upon second-hand items. And especially

clothes in the days before massed produced garments. The Marine Store Dealer was crucial

in catering to the daily needs of poorer communities.

'Marine Store Dealer' had

become a generic term for any kind of miscellaneous second-hand merchant supplying the

'lower orders'. It would be misleading to think of this as a peripheral trade, like junk

shops of the next century --which in some respects they resembled --because the majority

of poorer people were almost entirely reliant upon second-hand items. And especially

clothes in the days before massed produced garments. The Marine Store Dealer was crucial

in catering to the daily needs of poorer communities.But there were several aspects to the trade: firstly, as a cheap retail source of every manner of second-hand domestic goods --from clothes to cooking pans to bedding ; secondly, as unlicensed pawnbrokers to the poor, they would lend against small items of too little value to interest the legitimate pawnbrokers. This was a vital role in meeting the needs of the domestic economies of those whose only 'hockable' possessions might be a bent spoon or a tin mug or an old shirt or handkerchief. This illegal service was advertised by hanging a rag-doll in the window or by the door, in consequence of which they were known as 'Dolly Shops'. Thirdly, in the economy of nineteenth-century London, as in many third world cities today, there was virtually no such thing as 'waste' in the modern sense. Scarcely anything was thrown away, everything was recycled--(There were even 'dog-pure' women who went around the streets collecting dog muck in buckets for use in leather curing) --In some respects the Marine Store Dealer took much the role of the early twentieth-century 'rag and bone' man . But not only might he 'tott' the streets for 'any old iron, bottle and rags', but people would bring small amounts of all manner stuff to the shop --scullery maids could make a few pence 'on the side' by selling old kitchen fat, or the week's meat bones, which the Marine Store Dealer would keep until he had sufficient to 'sell on' for some obscure industrial use.

[ Mr Dickens gives a colourful description of just such a shop in his account of Mr Krook's premises in chapter five of 'Bleak House', and essays upon their differing character in various parts of the city in Chapter 21 of 'Sketches by Boz' ]

These two roles --of "Dolly Shop" pawnbroker, and universal recycler of 'unwanted' items, inevitably brought them a reputation with the authorities as the principal 'fences' for stolen goods --which when one also considers the localities in which they operated --they could scarcely avoid sometimes being.

But as an avocation it did bring a person into curiously intimate contact with the variety of life --and frequently with people 'in extremis'. Added to which, in an area such as Notting Hill was at that time, it was a reliable and potentially steadily profitable business.

But how did William Strong Darby fall into this trade?. The other popular name was 'Rag and Bottle Shops' - and the answer may lie here. A struggling tailor in a poor area in the economically volatile 1860s might soon discover that he could do better trade by patching up and selling second-hand clothes than by offering bespoke morning coats. This tack would lead almost inevitably to participation in the new street market that was just beginning to spring up on his doorstep, in the lower end of Portobello Lane, to which the poor from both Kensington and Paddington came shopping for old clothes and bric-a-brac. This in turn would introduce him to the world of the 'rag dealers', who bought up the discards that were fit only to be sold for paper manufacture, or to farmers as 'manure' -( there were no artificial fibres then --all clothes were 'organic'). Add to this that this was a man living with a stable downstairs where a horse and cart could be kept, and with two young teenage sons needing an occupation .........Such a man might soon become a Marine Store Dealer. And he might do well enough at it to take on extra premises, too.

Something very like this must have been the case.