But such was the eager confidence of the developers that they built streets of imposing stuccoed "shells" --the interiors to be finished when sold or leased-- the houses were designed to be middle and upper middle class family town dwellings. But that market was oversupplied, the hoped for buyers didn't come. At the southern end, up to about Chepstow Villas, they had some initial success. But to the north it was very patchy, a few houses were completed and occupied, but often soon abandoned, and not without reason.

Firstly, to the west, (where Elgin Crescent and Ladbroke Square Gardens now stand), was built a race course, which not

only proved a magnificent failure as a

business, but attracted most of London's ' low-life' on race days --and to the

consternation of 'respectability', overnight, too. While immediately to the north of that,

in a land of mire, into the soggy,cholera ridden brickfields running up to the canal, the

new railway, and the sulphurous Kensal Green Gas Works, had moved a large number of the

former inhabitants of the notorious inner London 'rookeries', --which were steadily being

demolished, to make way for the railways and the associated redevelopment of central

London-- but there being no obligation upon anybody to rehouse the displaced population,

they had made their own way to this attractive corner of North Kensington, already the

home of Irish pig breeders, 'totting' gypsies and itinerant brick makers. Here, in a vast

and sudden ramshackle shanty town, such as one sees today on the fringes of latin-american

cities, they had made their home. The area was known as the "Piggeries and

Potteries". It was estimated that there were as many pigs as people living in the

improvised shacks and tents. Many started to take up residence in the unfinished new

houses. When the wind was in the wrong direction, the smell over in Kensington High Street

was unbearable --( it was this that eventually led to something being done about

conditions [elementary drainage for one thing] ; and that out of self-interest, for it was

still widely believed that cholera was airborne; there was cholera in the "Piggeries

and Potteries", and if respectable folk could smell the air coming from there

.....Well ! -clearly, 'something had to be done').

only proved a magnificent failure as a

business, but attracted most of London's ' low-life' on race days --and to the

consternation of 'respectability', overnight, too. While immediately to the north of that,

in a land of mire, into the soggy,cholera ridden brickfields running up to the canal, the

new railway, and the sulphurous Kensal Green Gas Works, had moved a large number of the

former inhabitants of the notorious inner London 'rookeries', --which were steadily being

demolished, to make way for the railways and the associated redevelopment of central

London-- but there being no obligation upon anybody to rehouse the displaced population,

they had made their own way to this attractive corner of North Kensington, already the

home of Irish pig breeders, 'totting' gypsies and itinerant brick makers. Here, in a vast

and sudden ramshackle shanty town, such as one sees today on the fringes of latin-american

cities, they had made their home. The area was known as the "Piggeries and

Potteries". It was estimated that there were as many pigs as people living in the

improvised shacks and tents. Many started to take up residence in the unfinished new

houses. When the wind was in the wrong direction, the smell over in Kensington High Street

was unbearable --( it was this that eventually led to something being done about

conditions [elementary drainage for one thing] ; and that out of self-interest, for it was

still widely believed that cholera was airborne; there was cholera in the "Piggeries

and Potteries", and if respectable folk could smell the air coming from there

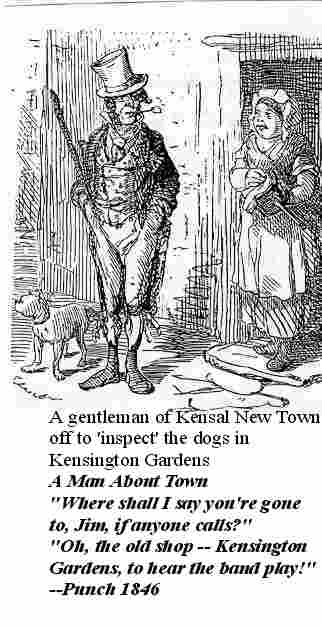

.....Well ! -clearly, 'something had to be done'). If all that wasn't enough, to the east, at the top of the little hedge lined

Portobello Lane -- then leading to Portobello Farm and the bridge over the canal -- was

the equally 'ill famed' Kensal 'New Town', reputedly home of the valorous regiments of

London's dog thieves, and where gambling on organized dog fights was the main occupation.

Regular large scale fights among the men, amounting to drunken riots, were famous, too.

The women seem to have been the breadwinners, working in Mr Knight's carpet beating yards

by the canal, or as washerwomen, which was the principal trade --( unless one includes

'dognapping', where the men would snatch high-class dogs in Kensington Gardens and pin up

ransom notes. Unfortunate unransomed dogs would simply be fed to the next batch of

hostages, making it a business requiring very little capital.)

If all that wasn't enough, to the east, at the top of the little hedge lined

Portobello Lane -- then leading to Portobello Farm and the bridge over the canal -- was

the equally 'ill famed' Kensal 'New Town', reputedly home of the valorous regiments of

London's dog thieves, and where gambling on organized dog fights was the main occupation.

Regular large scale fights among the men, amounting to drunken riots, were famous, too.

The women seem to have been the breadwinners, working in Mr Knight's carpet beating yards

by the canal, or as washerwomen, which was the principal trade --( unless one includes

'dognapping', where the men would snatch high-class dogs in Kensington Gardens and pin up

ransom notes. Unfortunate unransomed dogs would simply be fed to the next batch of

hostages, making it a business requiring very little capital.)Yet gradually order of sorts emerged from the chaos. Street by street, in patchwork fashion, the houses were finished, though mostly as houses of multiple occupation rather than the intended middle class family dwellings. The better houses attracted rather 'odd-ball' bohemian, sometimes 'blacksheep', members of the upper class, the artist WP Frith -( painter of the wonderful 'Derby Day')- being one notable example. German pork butchers opened up, and lady Italian mantua makers and French staymakers moved in, and from very early on there was a jewish community. Some of Napoleon's relatives arrived to live in Chepstow Villas.Theatrical types took upstairs rooms, and notices advertising 'Singing Lessons' started to appear in downstairs windows.

The several modest little mews built behind the large houses, whose private carriages and horses it was anticipated would be housed there, soon became instead the homes of northwest London's cabmen and horsekeepers and their ostlers, who brought with them their own distinct culture, not far removed from that of the old coachmen, which indeed, many were.

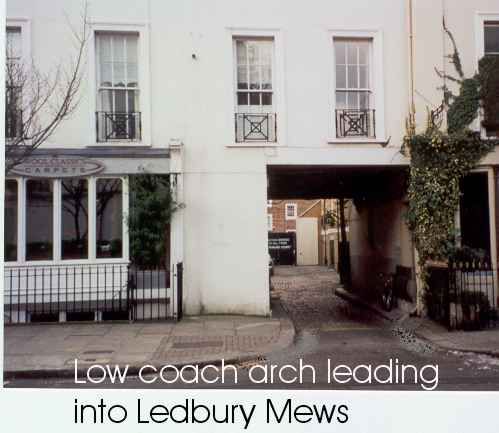

And it was into one of these, Ledbury Mews, (West) -- tucked behind the corner of the rather grand residential Chepstow Villas, and the more workaday Ledbury Road, less than a minute's

walk from Portobello Lane (now Road) -- that in 1856 or early

1857, the Darbys moved. They were among the first occupants, and there would remain Darbys

in this or other nearby mews for more than a hundred years. These were two and three room

dwellings over stables, all facing into a cobbled courtyard, entered from Ledbury Road

under a coach arch. Ledbury Mews was also graced by having a pub at its entrance.

walk from Portobello Lane (now Road) -- that in 1856 or early

1857, the Darbys moved. They were among the first occupants, and there would remain Darbys

in this or other nearby mews for more than a hundred years. These were two and three room

dwellings over stables, all facing into a cobbled courtyard, entered from Ledbury Road

under a coach arch. Ledbury Mews was also graced by having a pub at its entrance.

Inside the houses

nothing is left of the past. Most of the block of facing stables and cabmen's lofts with

their outside metal stairs have been rebuilt.)

Inside the houses

nothing is left of the past. Most of the block of facing stables and cabmen's lofts with

their outside metal stairs have been rebuilt.)