By 1871 William was fifty-one, and the forward

By 1871 William was fifty-one, and the forward  By 1871 William was fifty-one, and the forward

By 1871 William was fifty-one, and the forward momentum of his story naturally tends to pass to his children,

whose detailed biographies are not really part of this account. But as so much of their

lives, and their children's lives, were lived in that little mews, they were both the

stuff and the texture of his daily life. William junior was the first to marry; his wife

was Eliza Cook Jones, daughter of a seafaring family, who must have been named after the

poet, Eliza Cook, whose "Old Armchair" was a popular recitation piece. The first

of their children, Harry Darby, was born in 1875. Then at the end of 1876, Arthur married

Alice Amelia East, daughter of the previously mentioned Kensal Green tailor. The service

was performed at St Peter's Church by the Rev. Thomas Evans. The rather snobby --albeit

'bohemian'-- daughters of Mr Frith, the famous artist and neighbour, made a joke out of

this good natured clergyman's tendency to 'drop' his 'H's, --they called him "Good

'Evans".

Soon there are more grandchildren playing on the cobbles : Arthur and Alice's daughters, Alice Maude and Ada Elizabeth, and their cousin, William junior's daughter, Rose. And there will be plenty more.

And so passed the 1870s, lived out in the enclosed mews yard to the rhythm of cabs and carts coming and going, the laughter and squabbling of small children, the chink of empty bottles, the sounds and smells of steaming horses and sweet hay and oiled leather and sour straw, and the cloying reek of stacked dung- (carted away weekly)- And the flies. And the daily round of stabledoor chats with his neighbours : Jim Quinney, a coachman, and from Essex, too, living next door to Arthur and Alice, who were now in number 7; Charlie Goodwin at number 1, a coach painter; Bill Sallans, a horsekeeper at number 4; William Brace, stableman; Bill Brett, farrier; John Coxam, foreman cabby; George Haughton, coachman; Bob Page, stableman...........While the women, living aloft, would talk among themselves across the yard, leaning from upstairs windows -- (the origin of the expression "to hang out with") -- keeping an eye on the toddlers below, and a count of the jugs of beer going into number 9.

At some point around the end of the decade, Elizabeth perhaps started to hang out less frequently. We know little more than that Dr Mair -( formerly of the Indian Service, but now 'round the corner')- diagnosed 'Disease of the Brain'. Perhaps it was a tumour, or one of the many forms of meningitis that were common complications of other infections, especially TB.

Earlier in

the year, at the time of the census, Selina, by now married, was back at number 2, which

might suggest she was nursing her mother. But perhaps the onset was sudden. Either way, in

July, 1881, Elizabeth Darby died. Did she travel back in her imagination -away from the

London din- to those peaceful nightingale thronged woods  capping

the brow of green GalleyHill, and the clay and timber cottage of her youth ? Maybe. Though

the sad truth of victorian death makes it just as likely that her fever brought to her

brain the gunpowder factory explosions, and blazing men falling from the sky. Perhaps she

thought of little Elizabeth Strong, resting in the Essex soil among her country kin.

capping

the brow of green GalleyHill, and the clay and timber cottage of her youth ? Maybe. Though

the sad truth of victorian death makes it just as likely that her fever brought to her

brain the gunpowder factory explosions, and blazing men falling from the sky. Perhaps she

thought of little Elizabeth Strong, resting in the Essex soil among her country kin.

William bought a family plot up the road in Kensal Green. She was the first of many to be planted there. A rather shadowy figure while being nonetheless a real presence, she died young, at 58, by the standards of her family: her farm labourer father being officially at least 84 when he died in 1862 --he may actually have been born in 1776, and her mother reached nearly 80. But Elizabeth bequeathed her facial features, recognisable in her son Arthur, and in grand-daughters Alice-Maude and Ada-Elizabeth.

Inevitably one has the sense of William entering a long twilight, a widower, in his sixties at the beginning of the 1880s, his sons perhaps taking more control of the business-- when they weren't falling out. Selina had married Bill Brookman, a former sailor but now an imposing bearded policeman in 'F' Division. (They moved up Ladbroke Grove into a new little ten house long cul-de-sac, just off Lancaster Road, famous in the next century for something quite different : Rillington Place).

Angelina quietly vanishes from the story. Little Wally Gilbey, made rich by mother's ruin, gets a knighthood, and returns to old Essex as Sir Walter, a landed toff. ( And does what? --He writes books about horses and coaches, of course.) We know William was close to all his grandchildren. At Victoria's first 'Jubilee', in 1887, he bought them sets of commemorative coins-- ( which introduced the new four and two shilling pieces in anticipation of imminent decimalisation, which came rushing in about eighty years later).

But that twilight image may be misleading. He was an active, alert, man, he may have frustrated William junior by holding the reins, both literal and metaphorical, till the very end. He had a sly humour, and he could tell a good tale. And in the beginning of the 'nineties, he acquired a ready audience in the form of Arthur's youngest son, Teddy. They became one of those sparky January and December couples, the bright, cheeky, never more than jockey sized lad, and the old man from another age, who reckoned he was descended from a court jester, were put together during long days, in each other's custody. And when the old man spoke : of stage coaches stuck in the snow, of the world before steam-trains, of streets before lights, before policemen even; of the little tailor's 'trotter' running through the Georgian streets with a parcel of cloth under his arm, like another Oliver Twist looking out with anxious alarm for any real life Bill Sikes in the shadows; of officers bound for the Crimea walking down Bond Street in their new, perfectly cut raglans; of how to work a 'four in hand' : when he spoke of these things,Teddy listened.

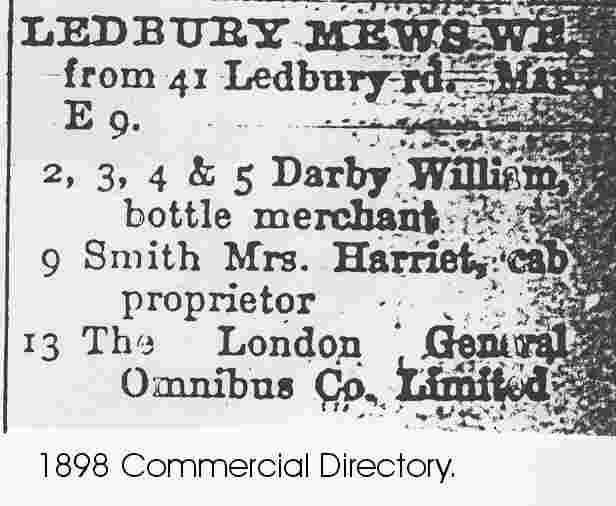

Others may

have been too busy. Towards the end of the century William junior became more of a  presence, describing himself in some trade directories as a "Wine Cooper

and Bottle Merchant" (that was his style)- and the business address comprised a

considerable proportion of the southern wing of the Mews. Family came and went and came

back again. One day Arthur's daughter, Ada, brought home an enigmatic,

presence, describing himself in some trade directories as a "Wine Cooper

and Bottle Merchant" (that was his style)- and the business address comprised a

considerable proportion of the southern wing of the Mews. Family came and went and came

back again. One day Arthur's daughter, Ada, brought home an enigmatic, but very plausible young man, working at a nearby hotel : a 'romancer',

thought Teddy, the sort of man who invented himself as he went along; he was calling

himself John Alfred Holdoway, he moved into number 1, and in the spring of 1901, he and

Ada were married. It was just a month after Queen Victoria had died. William had lived on

into yet another world. Ada brought two

but very plausible young man, working at a nearby hotel : a 'romancer',

thought Teddy, the sort of man who invented himself as he went along; he was calling

himself John Alfred Holdoway, he moved into number 1, and in the spring of 1901, he and

Ada were married. It was just a month after Queen Victoria had died. William had lived on

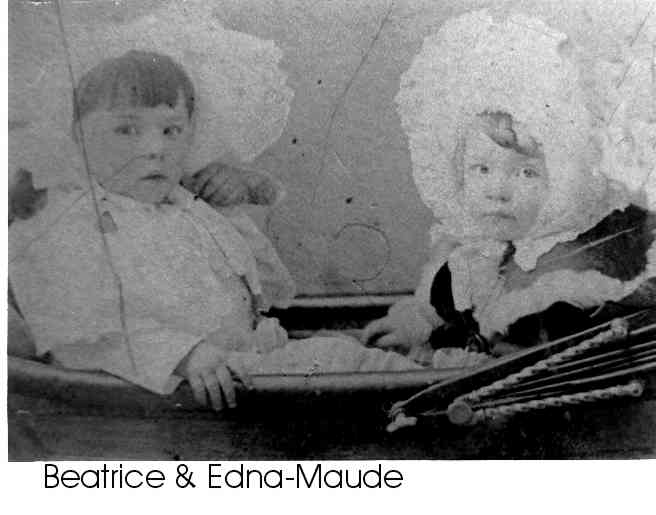

into yet another world. Ada brought two  great-grand-daughters

to show him : Beatrice in 1902, and Edna-Maude in 1903. They were dandled in the old hands

that had themselves brushed other hands that had held the world of the 1750s and 60s: yet

those little girls would live to see men on the moon.

great-grand-daughters

to show him : Beatrice in 1902, and Edna-Maude in 1903. They were dandled in the old hands

that had themselves brushed other hands that had held the world of the 1750s and 60s: yet

those little girls would live to see men on the moon.

On July the

twenty-third, 1903, William Strong Darby died. His life was almost conterminous with that

of Queen Victoria, although he was two years older than she had been when he died. Only

eight or nine years younger than Dickens, he had outlived him by more than thirty years.

And as the Gilbeys had retired to their country  estates in Essex,

so William Strong Darby retired to his, too : a few yards of shady green in Kensal Green

Cemetery, midway between the tomb of the Duke of Sussex and the Kensal Green Gas Works.

estates in Essex,

so William Strong Darby retired to his, too : a few yards of shady green in Kensal Green

Cemetery, midway between the tomb of the Duke of Sussex and the Kensal Green Gas Works.

Thanks to Selina, who kept an album of photographs dating back to the 1860s, we can put faces to William and his family. And thanks to Teddy --the little lad who went on to 'handle horses' as a London horse-bus driver before 1914, and in France during the First War; and who even as a chirpy old gentleman in the 1960s, was still being sent for by local undertakers as a driver whenever a horse-drawn hearse had been requested-- thanks to him, we have a real sense of old William's personality. And that personality fits the photographs and shines out from them.

The Darbys made a small mark in Notting Hill : Teddy lived out his own long life in its mews. Just round the corner, in Chepstow Villas, before the First War, Charles Dickens' grandson and his family came to live, and there grew up Monica Dickens, the novelist. In her writings about her childhood she speaks of 'the naughty Darby boys' who lived in the mews behind the house. And in one of her novels, when she needed a name for a young villain, she called him 'Darby'. Old William would surely have enjoyed that.

KH 2001