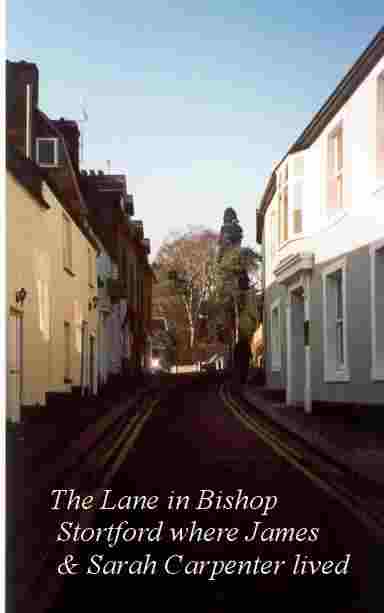

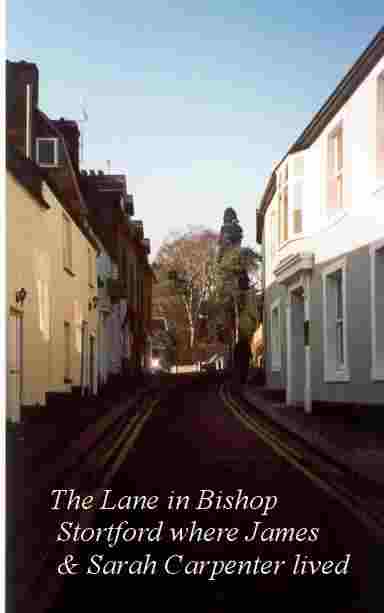

His time in Stortford would probably

have been spent among foaming horses, carpenters' timber, harness leather, and a noisy

extended family : the  Carpenters had children of their

own, and a few doors away lived the Handscombes, one of whose sons was father of Angelina,

a 'base-born' daughter of Maryanne Darby of Hallingbury, probably another of Jane's

sisters. (In this case both (!) parents were taken before the JP for not making

contributions to the parish for their daughter's upkeep. This was not that uncommon.)

Angelina, too, may have been 'brung up' by the more settled Sarah, with help from the

parish. And there were the Tylers. The Gilbeys, however, had started to go somewhat 'up'

in the world.

Carpenters had children of their

own, and a few doors away lived the Handscombes, one of whose sons was father of Angelina,

a 'base-born' daughter of Maryanne Darby of Hallingbury, probably another of Jane's

sisters. (In this case both (!) parents were taken before the JP for not making

contributions to the parish for their daughter's upkeep. This was not that uncommon.)

Angelina, too, may have been 'brung up' by the more settled Sarah, with help from the

parish. And there were the Tylers. The Gilbeys, however, had started to go somewhat 'up'

in the world.

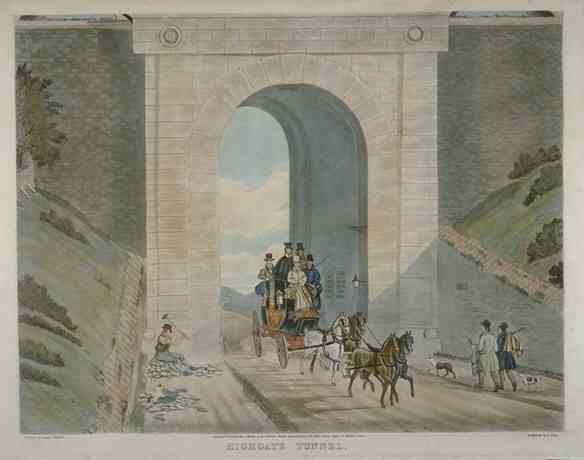

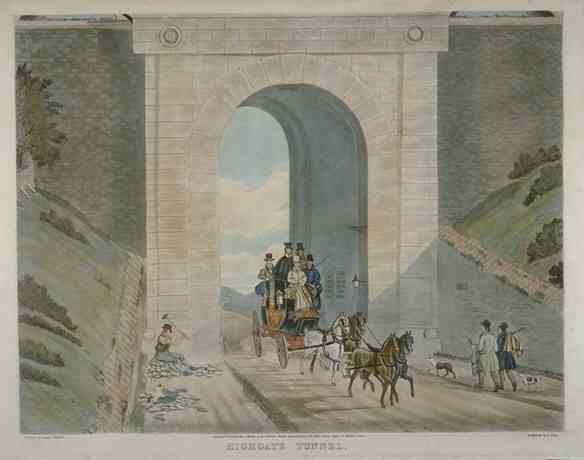

One ride on Henry

Gilbey's stage, though, took William away to another life: he was sent to be an apprentice

tailor in London. It was quite usual for boys in this trade to be indentured in London;

even in Colchester, the old centre of Essex tailoring, it was accepted that only by

working in London could a tailor be brought 'up to speed'. This would have been almost

certainly in 1833 or 1834, making William the more or less exact contemporary of the

fictional Oliver Twist, whose own brief apprenticeship with Sowerby, the undertaker, and

flight into the clutches of Fagin, was set in about that year. Like Oliver, William

may have begun his career sleeping under the shop counter, and lifting down the window

shutters in the grey dawn. One can read that book for a vivid child's eye view of

the London of the time.

One ride on Henry

Gilbey's stage, though, took William away to another life: he was sent to be an apprentice

tailor in London. It was quite usual for boys in this trade to be indentured in London;

even in Colchester, the old centre of Essex tailoring, it was accepted that only by

working in London could a tailor be brought 'up to speed'. This would have been almost

certainly in 1833 or 1834, making William the more or less exact contemporary of the

fictional Oliver Twist, whose own brief apprenticeship with Sowerby, the undertaker, and

flight into the clutches of Fagin, was set in about that year. Like Oliver, William

may have begun his career sleeping under the shop counter, and lifting down the window

shutters in the grey dawn. One can read that book for a vivid child's eye view of

the London of the time.

That London, before the railways came,

though in hectic transition, was in its fabric, its atmosphere, indeed, many of its

people, still the Georgian London of Hogarth and Dr Johnson. The occasional elderly

gentleman, clinging to the fashions of his youth, in knee breeches and powder wig, three

cornered hat and buckle shoes, might still be seen amid the throng of young fellows in

'beavers' (top hats), and --in the opinion of the old gentlemen -- the rather

unnecessarily 'new-fangled' leg wear, called 'trowsers'.

(Trousers and 'Tall Hats' had become the norm among

the smart set in London in the decade after Waterloo.) All these fashions William would

soon have to learn, quite literally, 'inside-out'.

One noteable feature was the din : the noise of modern traffic is as nothing compared with

the rumble, rattle, clatter and scrape of thousands upon thousands of iron-tyred

cart wheels and iron-shod hooves, on the stone roads of the city and many London

brewers still transported their barrels on screeching iron-runnered sledges

rather than wheeled drays.

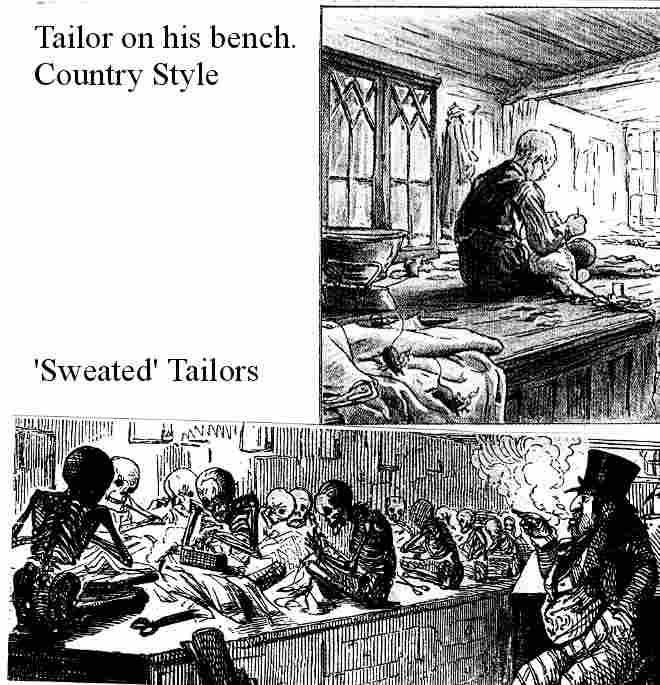

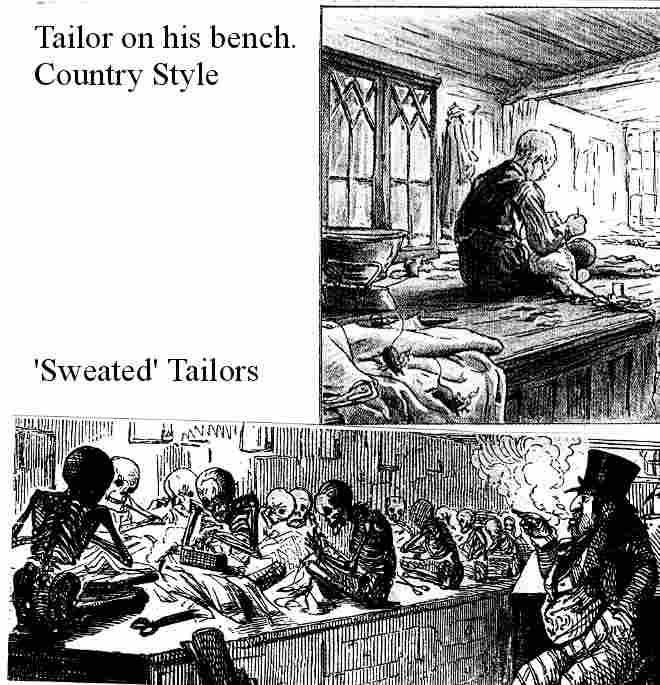

It was, however, a most extraordinary time to be entering the London tailoring trade :

1834 saw a crisis in a long, bitter, dispute, and an historic strike by the journeymen

tailors of London -one of the first major strikes in a modern sense in any industry. It

was a rearguard action by those trying stop a rapid decline into a 'sweated' trade, and to

maintain the traditional standards of work and agreements on pay, following what was in

effect the 'deregulation' of the industry by government legislation in 1813. The men

were divided into the 'flint', or 'honourable', masters and operatives, who were

'time-served', and worked 'by the book' --'on the log', they called it-- and the 'dung'

men, who undercut the 'going rate', and farmed out work at ever decreasing levels of pay.

'Cutting' and "sewing' tailors at this time worked seated  cross legged on

benches, and because they needed constant use of their hot irons for pressing, stretching,

and shaping material, and because in the days before electricity or gas, those irons had

to be constantly heated on stoves or coke braziers, even in the height of summer, they

frequently worked stripped to their 'small clothes', or even stark naked. It was when they

were crammed into small, overcrowded, work rooms in these conditions, that the term

"sweated trade" was coined. (It was a little later applied to piece work cabinet

makers, too, who in similar conditions, working in cellars or garrets, needed to 'boil'

their glue.) To be a 'knight of the needle' was to be in a very unhealthy trade : early

government health committees found that consumption (TB) was endemic among sewing men,

while many were unable to continue beyond their forties because of failing eyesight. They

did have strong backs, though, it was reported --apparently as a consequence of their

cross legged sitting habits.

cross legged on

benches, and because they needed constant use of their hot irons for pressing, stretching,

and shaping material, and because in the days before electricity or gas, those irons had

to be constantly heated on stoves or coke braziers, even in the height of summer, they

frequently worked stripped to their 'small clothes', or even stark naked. It was when they

were crammed into small, overcrowded, work rooms in these conditions, that the term

"sweated trade" was coined. (It was a little later applied to piece work cabinet

makers, too, who in similar conditions, working in cellars or garrets, needed to 'boil'

their glue.) To be a 'knight of the needle' was to be in a very unhealthy trade : early

government health committees found that consumption (TB) was endemic among sewing men,

while many were unable to continue beyond their forties because of failing eyesight. They

did have strong backs, though, it was reported --apparently as a consequence of their

cross legged sitting habits.

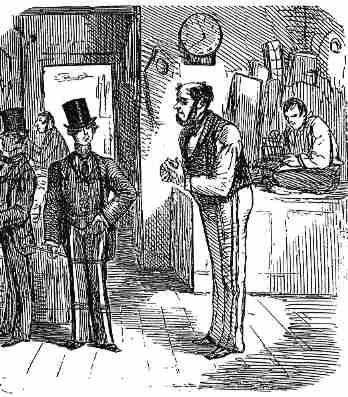

As an apprentice, he would have served seven years before becoming a time-served

journeyman tailor, which would have been in about 1841. We do not know where, or with

whom, he served his time. The centres of London tailoring were in the 'west', around

Bond Street and Savile Row, where the best cutting men worked; in

Soho, where they tended to send the patterns and material to be sewn in somewhat less

salubrious surroundings; and in the city proper and its easterly fringing villages,

rapidly becoming the 'east-end'. Many Essex lads worked in this eastern area which was

contiguous with that county, the Essex boundary at that time being the Lee crossing at Bow

Bridge. But he may well have worked in any or even all of these places. As a 'prentice, he

would have started out as a 'trotter', collecting material from the drapers and delivering

finished articles to customers, so the London streets and their 'Artful Dodgers' and 'Poor

Joe' the crossing sweepers would have become very familiar to him. His years of long hours

of monotonous sewing -- 6am to 7 or 8 at night would have been leavened by endless talk :

it being a 'quiet' trade, tailors were great talkers; they would often club together to

employ a boy or old fellow to read the newspapers to them as they worked, and then debate

--or simply argue about--the day's news.

Bond Street and Savile Row, where the best cutting men worked; in

Soho, where they tended to send the patterns and material to be sewn in somewhat less

salubrious surroundings; and in the city proper and its easterly fringing villages,

rapidly becoming the 'east-end'. Many Essex lads worked in this eastern area which was

contiguous with that county, the Essex boundary at that time being the Lee crossing at Bow

Bridge. But he may well have worked in any or even all of these places. As a 'prentice, he

would have started out as a 'trotter', collecting material from the drapers and delivering

finished articles to customers, so the London streets and their 'Artful Dodgers' and 'Poor

Joe' the crossing sweepers would have become very familiar to him. His years of long hours

of monotonous sewing -- 6am to 7 or 8 at night would have been leavened by endless talk :

it being a 'quiet' trade, tailors were great talkers; they would often club together to

employ a boy or old fellow to read the newspapers to them as they worked, and then debate

--or simply argue about--the day's news.

As a journeyman, he would have needed to join a tailor's 'house of call'. This was a

public house wherein was kept a book which listed the names of the local time served men.

To this house the 'honourable' master tailors would apply when they needed men, and would

have to take the first available men from the list. It was in this sense a 'closed shop' :

it needed to be : employment was very uncertain; men were typically taken on by the day or

half day, and were constantly in danger of losing work to the 'sweated' men, who would

take it home with them, and by getting their wives and children to do the sewing

overnight, would do the job in half the time, and often for a much reduced price : this

way they undercut one another into hopeless penury. But even the best 'house of call'

tailors would expect to be out of work for at least three or four months in the year. It

was an industry subject to drastic fluctuations in demand. And as they might spend up to

half their working lives in a public house, waiting for 'a call', drink was a major

problem.

Carpenters had children of their

own, and a few doors away lived the Handscombes, one of whose sons was father of Angelina,

a 'base-born' daughter of Maryanne Darby of Hallingbury, probably another of Jane's

sisters. (In this case both (!) parents were taken before the JP for not making

contributions to the parish for their daughter's upkeep. This was not that uncommon.)

Angelina, too, may have been 'brung up' by the more settled Sarah, with help from the

parish. And there were the Tylers. The Gilbeys, however, had started to go somewhat 'up'

in the world.

Carpenters had children of their

own, and a few doors away lived the Handscombes, one of whose sons was father of Angelina,

a 'base-born' daughter of Maryanne Darby of Hallingbury, probably another of Jane's

sisters. (In this case both (!) parents were taken before the JP for not making

contributions to the parish for their daughter's upkeep. This was not that uncommon.)

Angelina, too, may have been 'brung up' by the more settled Sarah, with help from the

parish. And there were the Tylers. The Gilbeys, however, had started to go somewhat 'up'

in the world. One ride on Henry

Gilbey's stage, though, took William away to another life: he was sent to be an apprentice

tailor in London. It was quite usual for boys in this trade to be indentured in London;

even in Colchester, the old centre of Essex tailoring, it was accepted that only by

working in London could a tailor be brought 'up to speed'. This would have been almost

certainly in 1833 or 1834, making William the more or less exact contemporary of the

fictional Oliver Twist, whose own brief apprenticeship with Sowerby, the undertaker, and

flight into the clutches of Fagin, was set in about that year. Like Oliver, William

may have begun his career sleeping under the shop counter, and lifting down the window

shutters in the grey dawn. One can read that book for a vivid child's eye view of

the London of the time.

One ride on Henry

Gilbey's stage, though, took William away to another life: he was sent to be an apprentice

tailor in London. It was quite usual for boys in this trade to be indentured in London;

even in Colchester, the old centre of Essex tailoring, it was accepted that only by

working in London could a tailor be brought 'up to speed'. This would have been almost

certainly in 1833 or 1834, making William the more or less exact contemporary of the

fictional Oliver Twist, whose own brief apprenticeship with Sowerby, the undertaker, and

flight into the clutches of Fagin, was set in about that year. Like Oliver, William

may have begun his career sleeping under the shop counter, and lifting down the window

shutters in the grey dawn. One can read that book for a vivid child's eye view of

the London of the time. cross legged on

benches, and because they needed constant use of their hot irons for pressing, stretching,

and shaping material, and because in the days before electricity or gas, those irons had

to be constantly heated on stoves or coke braziers, even in the height of summer, they

frequently worked stripped to their 'small clothes', or even stark naked. It was when they

were crammed into small, overcrowded, work rooms in these conditions, that the term

"sweated trade" was coined. (It was a little later applied to piece work cabinet

makers, too, who in similar conditions, working in cellars or garrets, needed to 'boil'

their glue.) To be a 'knight of the needle' was to be in a very unhealthy trade : early

government health committees found that consumption (TB) was endemic among sewing men,

while many were unable to continue beyond their forties because of failing eyesight. They

did have strong backs, though, it was reported --apparently as a consequence of their

cross legged sitting habits.

cross legged on

benches, and because they needed constant use of their hot irons for pressing, stretching,

and shaping material, and because in the days before electricity or gas, those irons had

to be constantly heated on stoves or coke braziers, even in the height of summer, they

frequently worked stripped to their 'small clothes', or even stark naked. It was when they

were crammed into small, overcrowded, work rooms in these conditions, that the term

"sweated trade" was coined. (It was a little later applied to piece work cabinet

makers, too, who in similar conditions, working in cellars or garrets, needed to 'boil'

their glue.) To be a 'knight of the needle' was to be in a very unhealthy trade : early

government health committees found that consumption (TB) was endemic among sewing men,

while many were unable to continue beyond their forties because of failing eyesight. They

did have strong backs, though, it was reported --apparently as a consequence of their

cross legged sitting habits. Bond Street and Savile Row, where the best cutting men worked; in

Soho, where they tended to send the patterns and material to be sewn in somewhat less

salubrious surroundings; and in the city proper and its easterly fringing villages,

rapidly becoming the 'east-end'. Many Essex lads worked in this eastern area which was

contiguous with that county, the Essex boundary at that time being the Lee crossing at Bow

Bridge. But he may well have worked in any or even all of these places. As a 'prentice, he

would have started out as a 'trotter', collecting material from the drapers and delivering

finished articles to customers, so the London streets and their 'Artful Dodgers' and 'Poor

Joe' the crossing sweepers would have become very familiar to him. His years of long hours

of monotonous sewing -- 6am to 7 or 8 at night would have been leavened by endless talk :

it being a 'quiet' trade, tailors were great talkers; they would often club together to

employ a boy or old fellow to read the newspapers to them as they worked, and then debate

--or simply argue about--the day's news.

Bond Street and Savile Row, where the best cutting men worked; in

Soho, where they tended to send the patterns and material to be sewn in somewhat less

salubrious surroundings; and in the city proper and its easterly fringing villages,

rapidly becoming the 'east-end'. Many Essex lads worked in this eastern area which was

contiguous with that county, the Essex boundary at that time being the Lee crossing at Bow

Bridge. But he may well have worked in any or even all of these places. As a 'prentice, he

would have started out as a 'trotter', collecting material from the drapers and delivering

finished articles to customers, so the London streets and their 'Artful Dodgers' and 'Poor

Joe' the crossing sweepers would have become very familiar to him. His years of long hours

of monotonous sewing -- 6am to 7 or 8 at night would have been leavened by endless talk :

it being a 'quiet' trade, tailors were great talkers; they would often club together to

employ a boy or old fellow to read the newspapers to them as they worked, and then debate

--or simply argue about--the day's news.